January 2023: A Big Bet on Clean Chips

In this edition:

- Avoiding Harmful Chemicals Using the Essential-Use Approach

- PFAS in Your Home… and Your Mouth?

- An Unwanted Ingredient: Chlorinated Paraffins

- New Year, New Laws, Healthier Products

- Green Science Policy Institute in the News

I hope you had an enjoyable holiday season and are having a good start to your new year. During the holidays, I enjoyed cross-country skiing in the tranquil Methow Valley of northern Washington and then 2023 began with a flurry of activity at our Institute around PFAS.

Recently chemical giant 3M announced its intention to stop manufacturing any PFAS. And last year, our joint papers on PFAS in cosmetics and in children’s uniforms contributed to California legislation to stop the use of PFAS in textiles and personal care products. PFAS production and harm should finally began to decrease—you would think. To the contrary, the PFAS producer Chemours is planning to greatly increase their PFAS production in North Carolina.

Chemours is justifying its expansion by pointing to the need for PFAS in domestic microchip manufacturing—an otherwise positive economic development championed by President Biden.

Pushing back against the expansion of PFAS manufacturing, I published an op-ed in The Hill lauding Biden for bringing microchip production home, but urging him to ‘build it back better’ by cleaning up the process and stopping the need for PFAS.

Our op-ed got the attention of White House advisors and we hope for progress on this and other PFAS issues this year. We are supporting the local North Carolina group Clean Cape Fear who are leading herculean efforts to stop the Chemours expansion. You can help by signing their petition to stop the increased production of PFAS.

Also, last week our Institute published a peer-reviewed paper advising a simple but revolutionary fix for regulating harmful chemicals in the U.S. and Canada. It’s called the essential-use approach and requires that chemicals of concern only be used where the use of the harmful substance in a product is “necessary for health, safety or is critical for the functioning of society” and where alternatives are not available.

For example, is using PFAS to make mascara waterproof necessary for health, safety, or the functioning of society? Of course not. This straightforward approach seems obvious, but it is a radical and important departure from the status quo which mostly considers function and cost when selecting chemicals.

Some trailblazing U.S. states and businesses have already begun applying the essential-use approach. For example, Maine recently banned the use of PFAS in all products by 2030, except where the state determines a use is “currently unavoidable.” Learn more about the essential use approach in our scientist Carol Kwiatkowski's op-ed in The Hill and in the blurb below. If you’re in manufacturing or retail, be sure to read our blog post on how businesses can leverage this approach.

Finally, if you’re looking for a new podcast, Frank A. von Hippel’s science history series is an excellent choice. I especially recommend his interview of our colleague Linda Birnbaum on the history of environmental health and another on planetary boundaries.

Wishing you a happy and healthy 2023,

Arlene and the Green Science Policy Team

Avoiding Harmful Chemicals Using the Essential-Use Approach

By Carol Kwiatkowski

The essential-use approach, a simple concept and an effective way to avoid harmful chemicals, can be summed up briefly: “If a harmful chemical isn’t necessary, don’t use it.”

Let’s unpack that. Harmful chemicals are known or suspected to be hazardous to people or wildlife, do not break down in the environment, accumulate in our bodies, or have other traits that raise red flags. Necessary means essential for health, safety, or the functioning of society. This definition of essentiality has been around since 1987 when it was developed for the Montreal Protocol to reduce the use of chlorofluorocarbons harming the ozone layer.

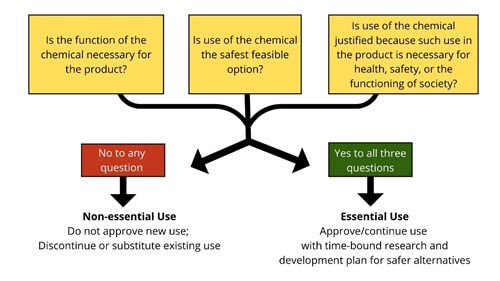

In our new peer-reviewed paper, we propose optimizing the essential-use approach for chemicals management by asking up to three questions, starting with whichever is easiest:

- Is the function of the chemical necessary for the product? Some functions like stain resistance in outdoor jackets are not essential and the use of the chemicals can be easily stopped.

- Is use of the chemical the safest feasible option? Sometimes safer alternatives are already available, like electronic receipts instead of paper receipts coated in bisphenols.

- Is use of the chemical in the product necessary for health, safety, or the functioning of society? Harmful chemicals can be essential until safer alternatives are developed (as in some personal protective equipment).

A ‘no’ answer to any of the three questions above indicates the use of the chemical is non-essential. Only chemicals that meet all three criteria with a yes answer are deemed essential--and only until safer alternatives are developed.

Think about it. If you’ve been reading our newsletters, you probably apply the essential use approach when you’re shopping. You look for safer options, you ask if you really need the function it provides, and you compare the use of the chemical to your need to be healthy and safe.

It’s time for governments and businesses to start doing the same.

PFAS in Your Home… and Your Mouth?

By Lydia Jahl

Did you know that PFAS can be found in some orthodontia? I was surprised to learn of this when reviewing 3M's recently published inventory of more than15,000 products that contain PFAS. The list was likely compiled to fulfill Maine’s 2023 reporting requirement for all PFAS-containing products.

Some of 3M’s PFAS uses are in common products perhaps found in your home. If you or a family member have had braces, fluoropolymer coatings could have been used on the ligature wires in your braces. Should young people have PFAS in their mouths for some years?

Other uses include most poster adhesives, hooks, and other products that use Command TM strips – small quantities of PFAS are likely used to help the adhesive strip detach from surfaces. Gift wrapping tape, aerosol propellants for some air fresheners, and certain whiteboard surfaces also use PFAS. These are all examples of PFAS uses that aren’t necessary – no one needs PFAS in their mouths or on a whiteboard!

Industrial uses include in hose fittings, valve assemblies, traffic sign paints, pavement-marking tape, abrasive products, cables, specialty tapes, architectural finishes, and molding additives for plastic parts. Products with the highest PFAS content include electronic cooling liquids and fluoropolymers like Teflon.

Other PFAS uses are in products important for health or safety. For example, bandages and medical patient warming gowns (including pediatric gowns) contain PFAS. Ironically, many products may expose us to PFAS even though the overall purpose of the product is to protect people from harmful substances, such as in certain respirator masks or water filtration systems. Safe replacements need to be developed for these uses as fast as possible.

While all PFAS producers need to take responsibility for the pollution and health harms caused by their chemicals, 3M’s disclosure regarding their PFAS usage and plans to phase out PFAS are steps in the right direction. We hope that other chemical manufacturers will follow.

An Unwanted Ingredient: Chlorinated Paraffins

By Lydia Jahl

Modern kitchens often contain numerous appliances to make the perfect gourmet meal. However, your kitchen may contain an unwanted ingredient: a class of flame retardants called chlorinated paraffins. These chemicals are toxic, persistent, bioaccumulative and listed for elimination in the Stockholm convention. Still they are produced in very high volumes and used in products as flame retardants, plasticizers and lubricants. Because of such uses, short-chain chlorinated paraffins, possible human carcinogens, have been detected in human livers, kidneys, fat, and breast milk.

In 2017, Swedish scientists found that 12 out of 16 hand blenders tested leaked chlorinated paraffins into food, likely from direct contact between the food and blender components. The researchers estimated that adults in Sweden using a hand blender once per day could increase their dietary intake of chlorinated paraffins up to 26 times their normal exposure from food.

Recent testing of many kitchen appliances found that chlorinated paraffins are commonly used to lubricate hinges in products such as refrigerators, microwave ovens, and food processors. In their study, brand-new appliances had the highest concentrations, suggesting chlorinated paraffins are released over time.

To reduce your exposure, clean products frequently, do not allow your food to contact the lubricant in appliances, and ventilate your kitchen while using a baking oven. Learn more about flame retardants and how to avoid them at our Six Classes website.

New Year, New Laws, Healthier Products

By Jen Jackson

Good news! A number of different states’ laws restricting PFAS have just gone into effect as of January 1st. These important laws will help reduce exposure to and environmental releases of these harmful chemicals – at least from new products introduced into those states.

Here’s a quick recap:

- Maine: PFAS is now banned in rugs, carpets, and fabric treatments sold or distributed in the state.

- New York: Paper-based plates, cups, bowls, and other food packaging may no longer contain PFAS.

- California: Like New York, California has banned PFAS in paper- and fiber-based food packaging. The same law also addresses PFAS and other chemicals of concern in cookware, requiring labels to list certain chemicals of concern in the product, and also no longer allows greenwashing claims on cookware that indicate a product is free of one PFAS (e.g. “PFOA-free!”) while another PFAS is in that product.

- Colorado: PFAS-containing firefighting foam is no longer allowed to be used at Federal Aviation Administration-designated public use airports.

Looking ahead, in July, another law banning PFAS in new children’s products, such as playpens, high chairs, nursing pillows and children’s mattresses, will go into effect.

Green Science Policy Institute in the News

By Rebecca Fuoco

Below are recent news articles, blogs, podcasts, newsletters, and more that have featured our Institute’s work and expertise.

- Our essential-use paper was featured in an article by Grace van Deelen for The New Lede. "The essential-use approach is the first feasible solution that will actually protect people and the environment before extensive damage is done,” our scientist Carol Kwiatkowski told her. Our paper was also featured in the popular Italian science news website Lega Nerd.

- Architectural Digest interviewed our communications director Rebecca Fuoco about California’s phase-out of PFAS in textiles. “Hopefully, manufacturers will get ahead of the curve and stop using forever chemicals even before the mandates kick in,” she told Christina Poletto.

- Our building materials report was recommended as a resource for construction workers in an article for The Maine Monitor by Marina Schauffler.

- Our executive director Arlene Blum gave a talk for a webinar put on by the Massachusetts Breast Cancer Coalition.

- California Assemblymember Phil Ting cited our study finding PFAS in school uniforms in his op-ed for the San Francisco Bay Times.

- Our building materials report was referenced in an article by Erin Rhoda about PFAS in plumbing tape for the Bangor Daily News.

- GreenBiz’s Jon Smieja recommended our www.SixClasses.org video series: "At the entry level, you can learn a lot about the toxic legacy of chemicals from the Six Classes, presented by the Green Science Policy Institute.”

- An explainer published in Sierra Magazine cited our work with Clearya finding PFAS in personal-care products.

- In its trade publication, the Advanced Textiles Association cited our studies on PFAS in cosmetics and textiles in its article on California’s phase-out of those uses.

- Our resources on flame retardants in furniture were recommended in an article for Thyroid Pharmacist.

- Our scientist Lydia Jahl spoke with Shannon Kelleher of The New Lede about 3M's announcement that they will stop manufacturing PFAS, noting that to truly have an impact beyond 3M's actions, we need to "stop all other [PFAS] uses and start cleaning up contaminated sites."

Receive Updates By Email

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter and get these updates delivered right to your inbox!